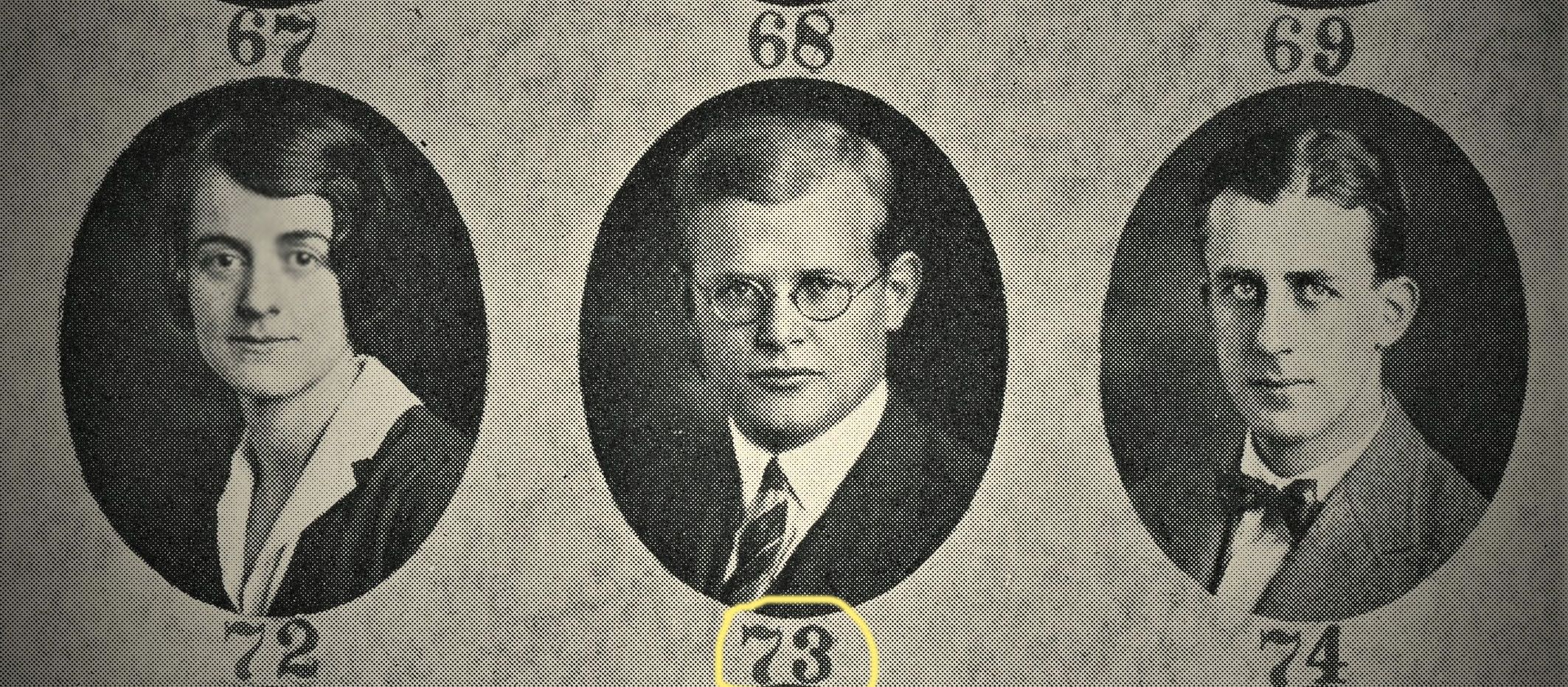

Dietrich Bonhoeffer ’31 in the Archives

“We are not to simply bandage the wounds of victims beneath the wheels of injustice, we are to drive a spoke into the wheel itself.”

Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s resident application, 1931 / I-House Archives

This Holocaust Remembrance Day, the International House Archives is proud to honor Alum Dietrich Bonhoeffer ’31 (1906-1945), who was a member of International House while pursuing a teaching fellowship at the Union Theological Seminary in New York. During this time, Bonhoeffer rooted himself in the realities of racism in the United States. He attended a Harlem Baptist church, took courses on social issues, read African American authors, and visited the American South. The lessons he gained from I-House, and his time in Harlem would prove foundational in his understanding of social justice and helped shape his views towards German antisemitism after the Nazi party came to power in the early 1930s. While a member of I-House, Bonhoeffer met Albert Franklin Fisher, a Black seminarian who invited him to Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, where he encountered the African American church experience. At the Church, Boneheoffer listened to Adam Clayton Powell preach the Gospel of Social Justice and formed a life-long love for Black Gospel music. He became an active member of the congregation, leading a women’s Bible study class and assisting weekly church school. Enmeshed in this vibrant community, Bonehoffer became deeply affected by the racism and injustice prevalent in America. He would later write, “This personal acquaintance with Negroes was one of the most important and gratifying events of my stay in America.”

Abyssinian Baptist Church, Harlem, NY

Bonhoeffer was an immediate opponent of National Socialism when Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933. He vehemently opposed the Third Reich’s political ideology, which turned Jesus into a divine representation of the ideal and allowed race-hate to become part of Germany’s religious life. After graduating from UTS, he became deeply involved in the Confessing Church, a movement that fought against the Nazification of the German Evangelical Church. In his essay, “The Church and the Jewish Question,” Bonhoeffer wrote on his church’s challenges under Nazism. He argued that Christians had an obligation to help all victims of injustice, regardless of their religion. Bonhoeffer began to preach on the virtues of action, decried the German church’s “cheap grace,” and heralded a “costly grace” — a grace that might cost a Christian their very life. In Bonhoeffer’s Black Jesus: Harlem Renaissance Theology and an Ethic of Resistance, Reggie Williams, Assistant Professor of Christian Ethics at McCormick Theological Seminary, theorizes Bonhoeffer was able to so clearly understand the evils of Nazism because he viewed it through the lens of Black American oppression.

German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945) / Photo by Bunk/ullstein bild via Getty Images

In service of the cause, Dietrich Bonhoeffer began work as an agent for Military Intelligence in October 1940, using his contacts to spread information about the resistance movement. In trips to Italy, Switzerland, and Scandinavia in 1941 and 1942, he informed messangers of resistance activities and tried to gain foreign support for the German resistance.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer Works series/ Fortress Press

While the deportation of Berlin Jews to the East began on October 15, 1941, Bonhoeffer wrote countless messages to foreign contacts and trusted German military officials, hoping that it might move them to action. Following this, Bonhoeffer became involved in “Operation Seven,” a plan to get Jews out of Germany by smuggling them into Switzerland using foreign papers. The Gestapo eventually discovered “Operation Seven,” and Bonhoeffer and his brother-in-law, Hans von Dohnanyi, were arrested in April 1943.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Cell 92

The German Reich charged Bonhoeffer with conspiring to rescue Jews, using his foreign travels for non-intelligence matters, and misusing his intelligence position to help Confessing Church pastors evade military service. They uncovered his connections to broader resistance circles and his ties to Hitler’s failed July 20, 1944 coup attempt. Transferred to a Gestapo prison in Berlin in February 1945, Bonhoeffer was taken to Buchenwald and moved to the Flossenbürg concentration camp in April. The German pastor was executed by the Nazi regime on April 9, 1945, just two weeks before the United States liberated the camp. When Bonhoeffer died, he famously remarked to another prisoner “This is the end — but for me, the beginning.” Further Reading- Bean, Alan. “The African-American Roots of Bonhoeffer’s Christianity,” Baptist News Global, 30 Oct. 2015.

- “Dietrich Bonhoeffer,” The Holocaust Encyclopedia.

- Myers, Ben. “Dietrich Bonhoeffer in New York,” Faith and Theology, 18 Oct. 2009.

Want to support the Archives? Click below! Have a question? Please email us at Archives@ihouse-nyc.org. Support the Archives