Japanese Internment in the Archives

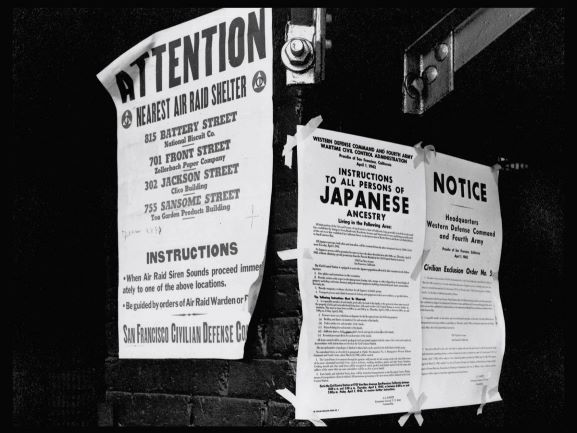

This month, in honor of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) History Month, the International House Archives examines one of the darker periods of American history, Japanese internment.

Want to support the Archives? Click below! Have a question? Please email me at Archives@ihouse-nyc.org. Support the Archives

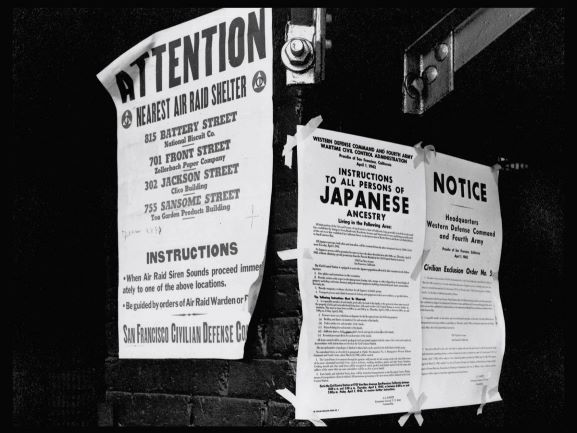

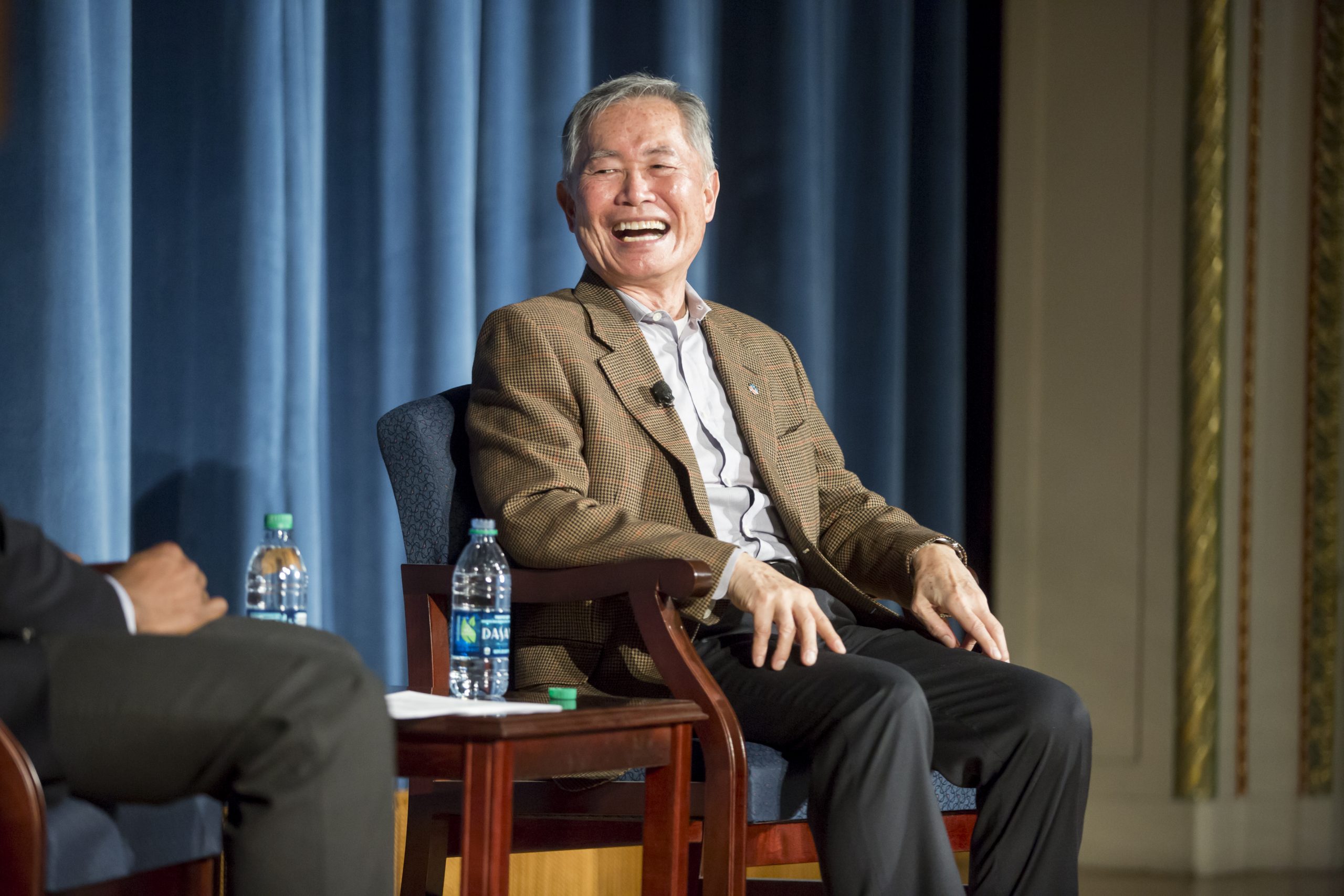

Dorothea Lange, San Francisco, California, April 11, 1942 / Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration.

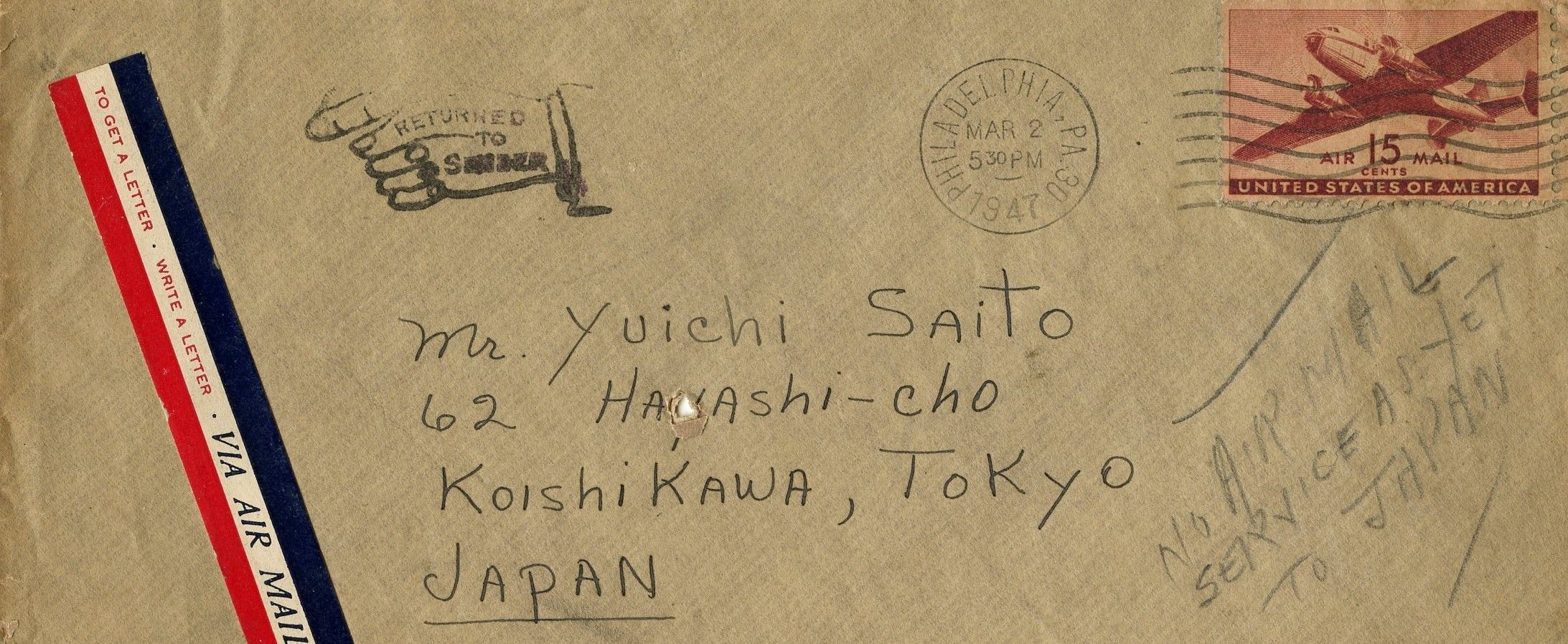

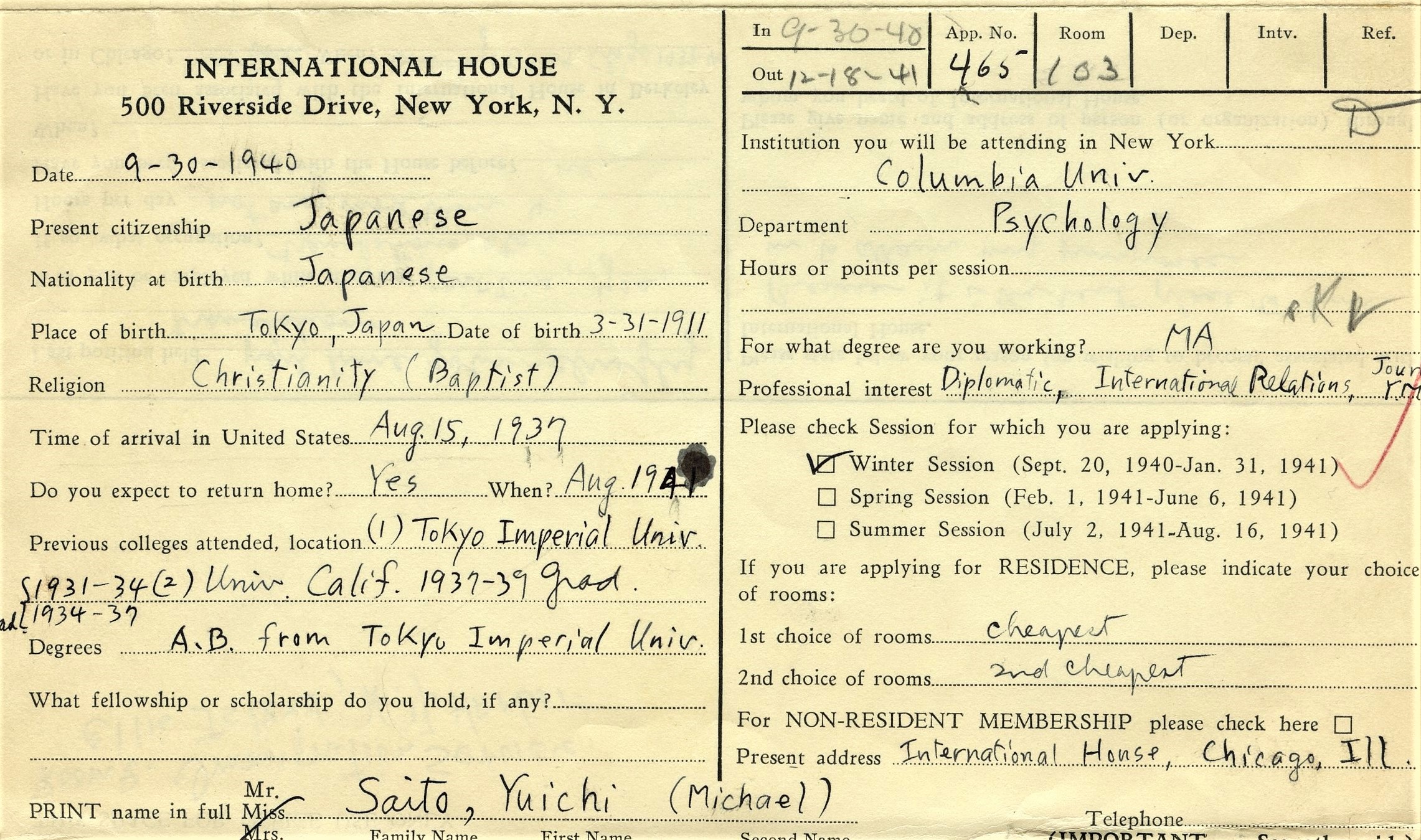

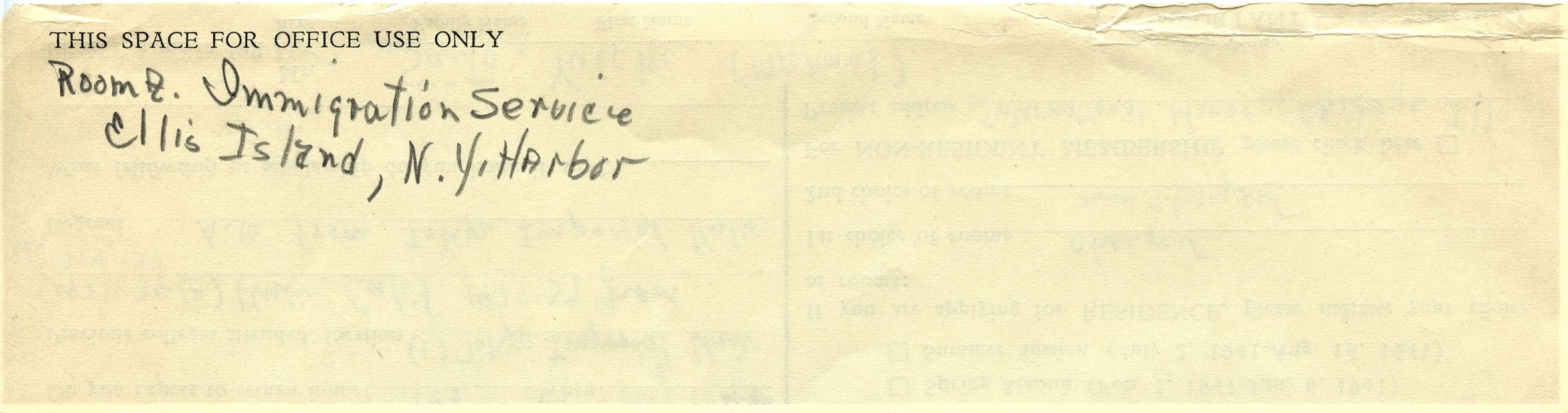

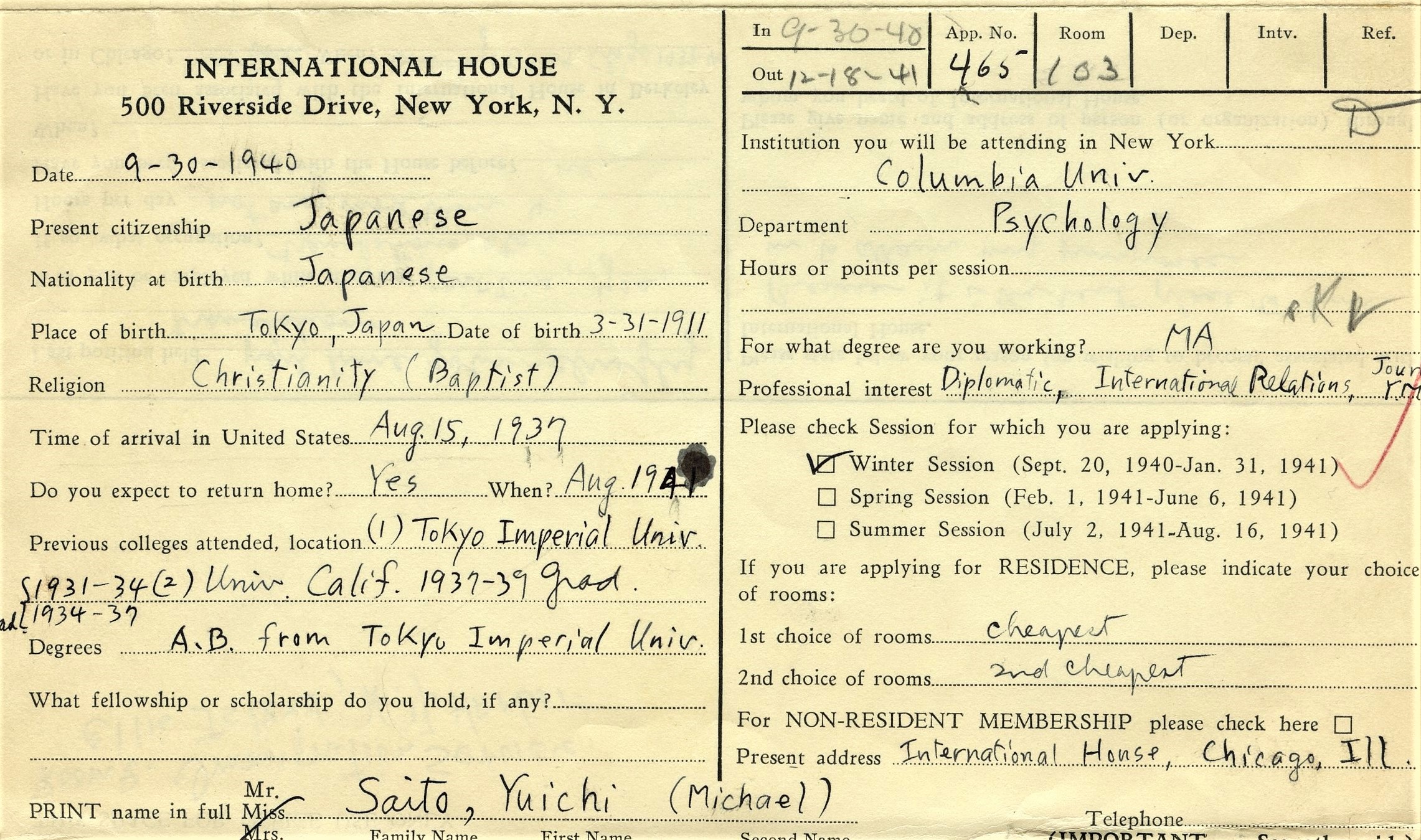

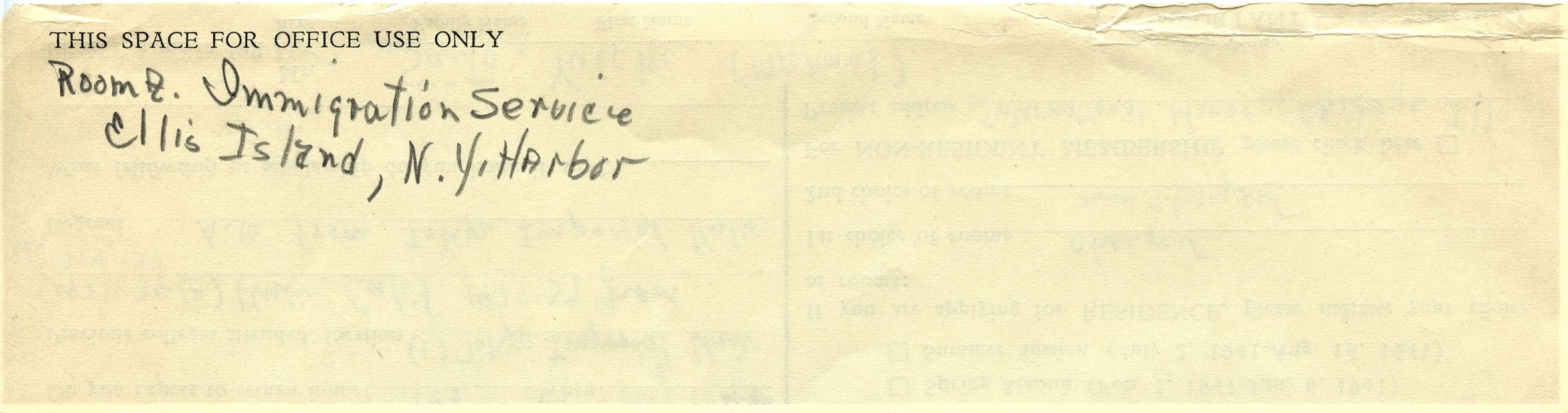

In the immediate aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the U.S. government began to round up and imprison Japanese Americans. Shortly after, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which forced all people of Japanese descent to leave their belongings and property behind and report to “relocation centers.” Between 1942 and 1945, in 10 internment camps located in isolated areas of California, Arizona, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and Arkansas, the government incarcerated over 120,000 Japanese Americans, most of whom were U.S. citizens and included women and children, the elderly, and the disabled. Although the imprisoned attempted to create a semblance of community, conditions in these facilities were harsh: barbed wire fences surrounded the perimeter, and armed guards had instructions to shoot anyone who attempted escape. As these events unfolded, International House was home to a number of Japanese residents. Though our records from this period are remarkably scant, by looking in the Archives, we can identify at least one resident who was arrested by the United States government. In the alumni files, a letter from Richard Loo on December 10, 1941, to former resident, Oreste Unti, reads: “Our friend Michael (Yuichi) Saito, the boy from Japan, was arrested by the F.B.I. a few nites ago. I am so sorry for him. It is really not his fault that his country is at war with us.” Saito’s admissions record reveals that he was detained only three days after the attacks on Pearl Harbor and transferred to Ellis Island.

Yuichi (Michael) Saito’s admission record, 1941 / I-House Archives

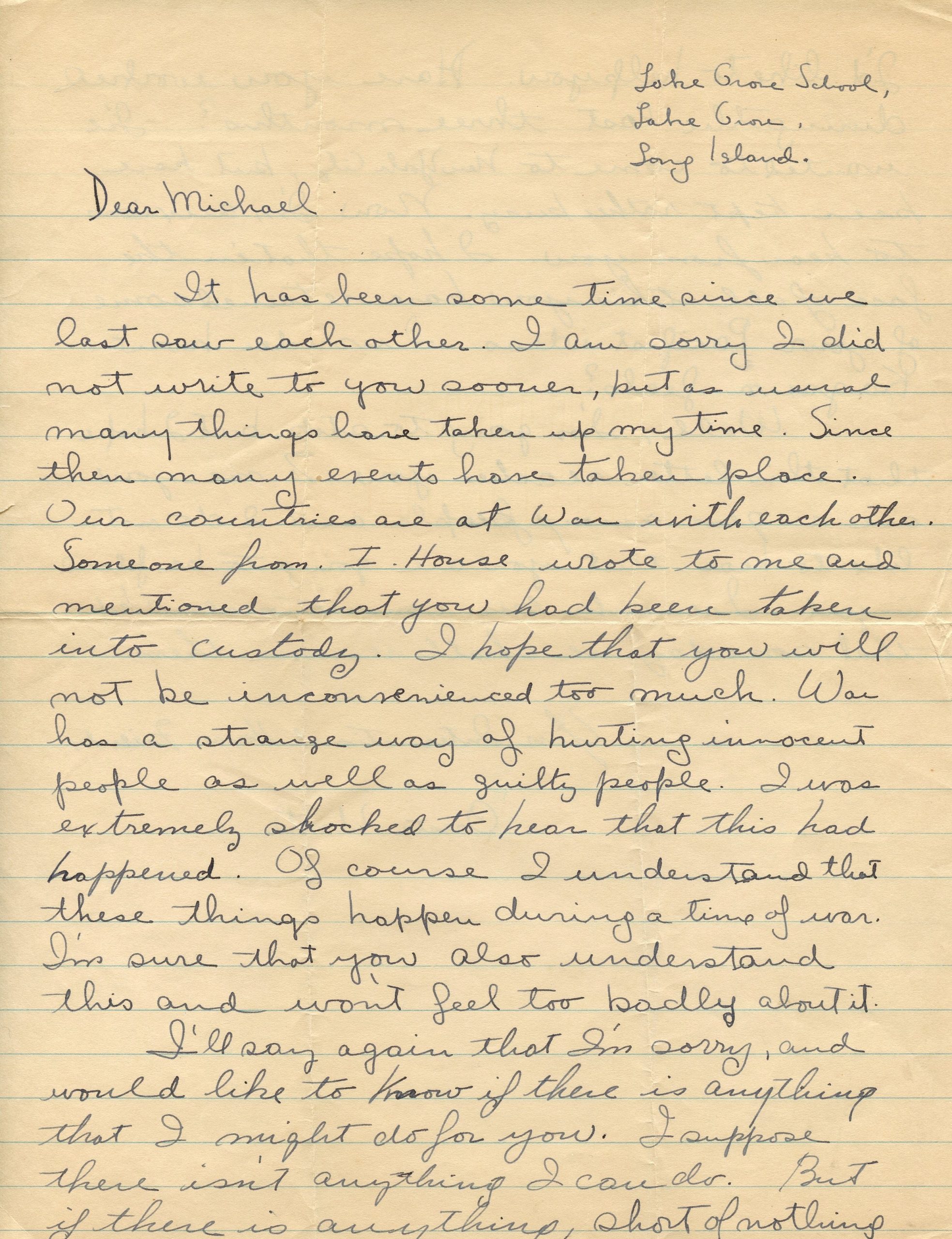

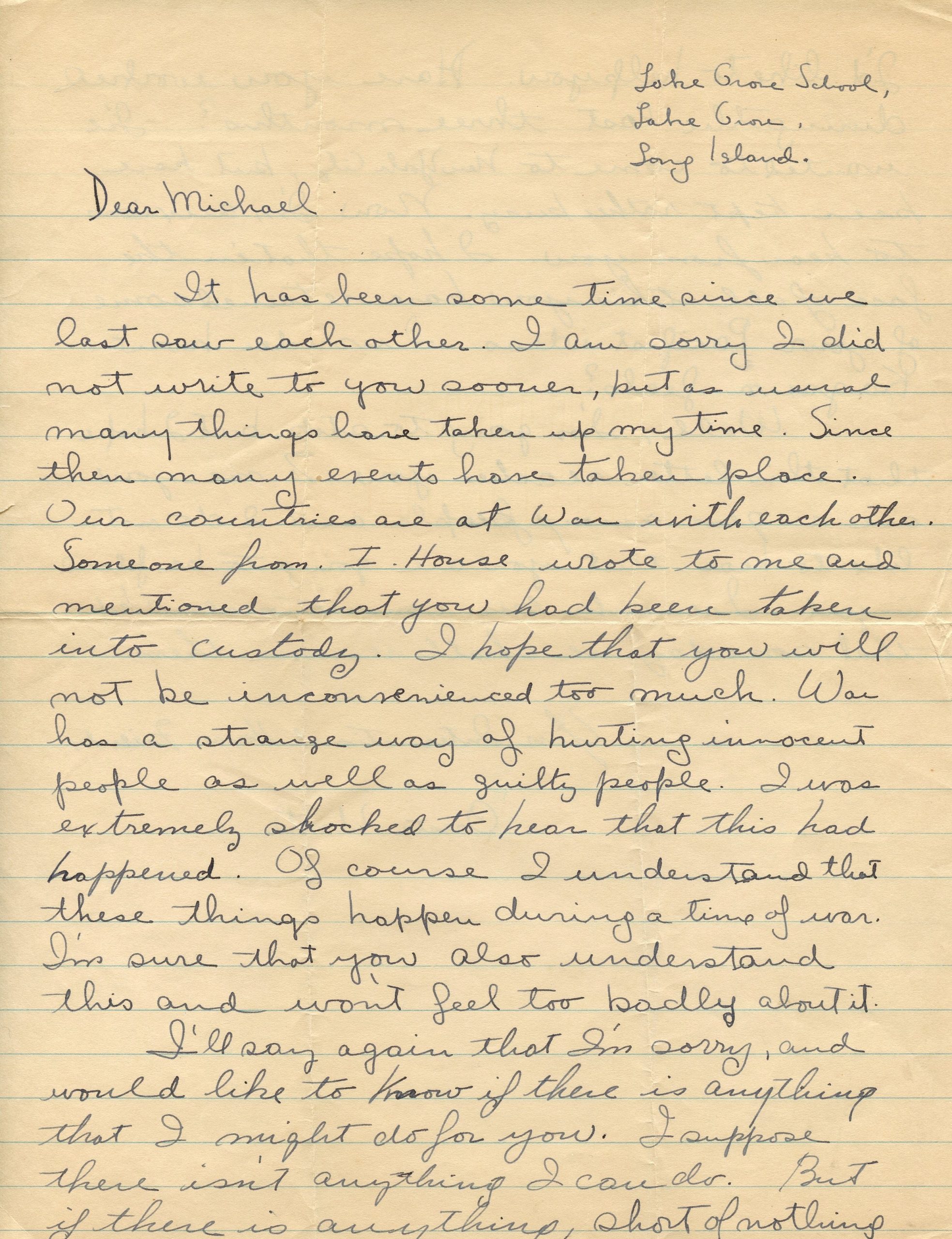

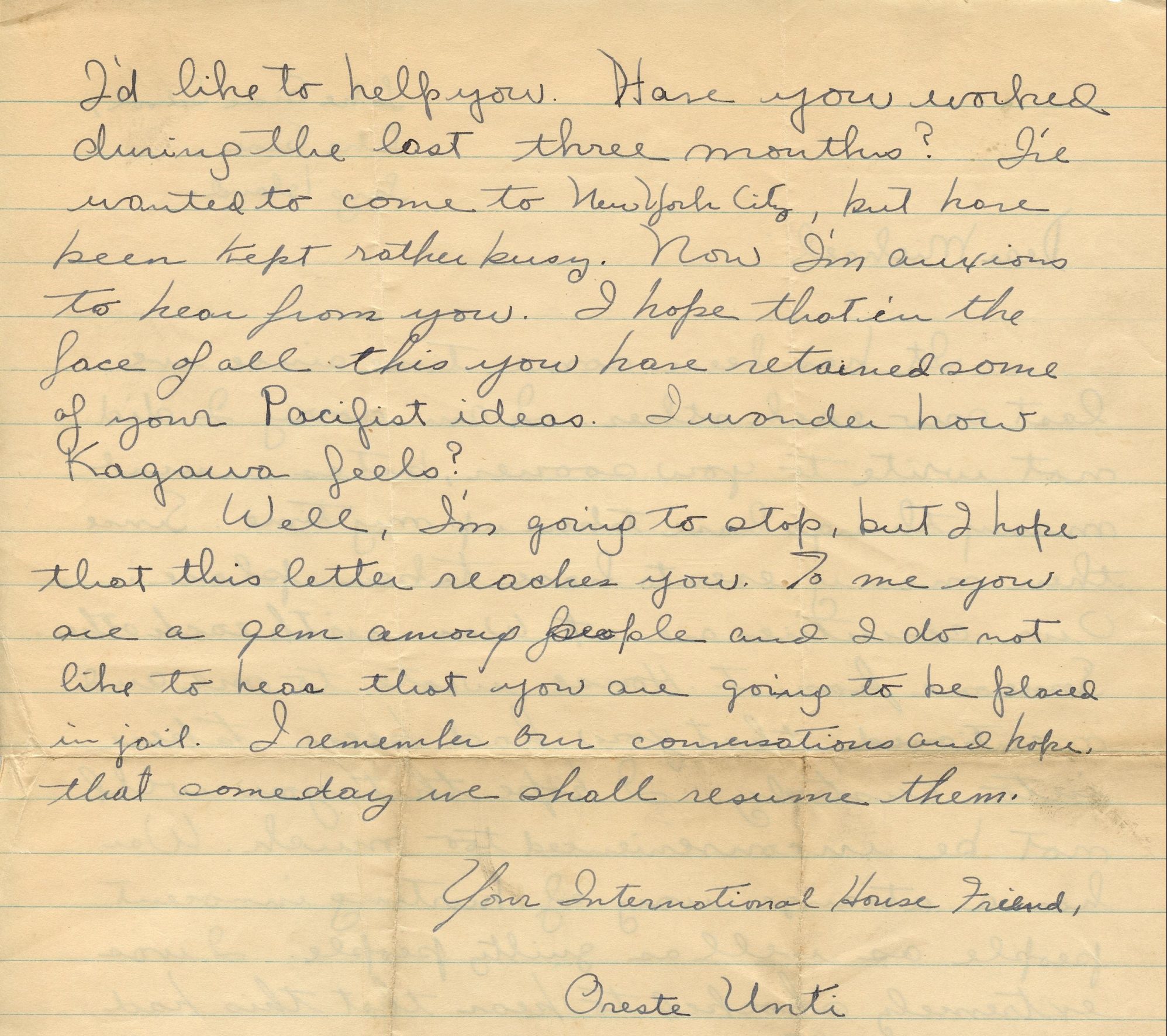

After he received this news, Unti wrote to Saito:“Someone from I-House wrote to me and mentioned that you have been taken into custody…I was extremely shocked to hear that this had happened…To me, you are a gem among people. I remember our conversations and hope that someday we shall resume them. Your International House friend, Oreste Unti.”

Oreste Unti to Yuichi Saito, 1941 / I-House Archives

Sadly, the Archives holds this piece of correspondence because this letter, along with others, never reached Saito.* During this period, while the government detained thousands of people of Japanese descent, the International House current and future Chairman of the Board of Trustees, Henry L. Stimson (1936-1948) and John J. McCloy (1954-1970), were responsible for shaping U.S. foreign policy. Serving under Stimson, McCloy was one of the key government officials who oversaw the placement of Japanese Americans in internment camps. Fearing espionage and acts of sabotage, McCloy insisted that a policy of removal was required to ensure public safety on the Pacific Coast. While he maintained that these centers were humane and necessary into the 1980s, history has revealed that McCloy’s actions were perpetrated by false reports and driven by public hysteria and racism.

Board of Trustees meeting in the Home Room with David Rockefeller, John J. McCloy, and Howard Cook, May 7th, 1957 / I-House Archives

Following the end of the war, the government released Japanese Americans, and many returned home to find their goods stolen and properties sold. Now considered a “grave injustice,” it wasn’t until 1983 that a special Congressional commission determined that the mass internment was a matter of racism and not military strategy. Later in the decade, President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, apologizing to the Japanese Americans and offering $20,000 to survivors of the camps. While Japanese internment is regarded as one of the most reprehensible violations of American civil rights in the 20th century, the legacy of these events endures today. Politicians and scholars continue to use this shameful period of history to further racist policies targeting immigrants and American citizens. As recently as 2016, in an attempt to establish a Muslim registry, Japanese internment camps were cited as a precedent by proponents of American president Donald J. Trump.

Notch and Margaret Miyake celebrating their 50th anniversary in the Home Room with other alumni/ I-House Archives

Activists like Notch and Margaret Miyake, who lived and met at International House in 1969, have made it their mission to combat xenophobia and broaden the public’s awareness of the Japanese-American experience of World War II. In 2015, the pair embarked on a road trip to the West, visiting the internment camps and detention centers that once housed more than 120,000 Japanese Americans. Notch Miyake said that “the trip became a pilgrimage” for him and Margaret Miyake as they began to realize the historical and spiritual importance of the camps. Speaking to Rochester’s Democrat & Chronicle, Margret Miyake said, “We wanted to see what remained of the camps and show and share with others. I don’t believe a lot of people know what happened to Japanese-Americans during World War II.” At the end of their trip, they documented and shared their experience in an exhibit titled “A Pilgrimage to the Japanese American Internment Camps of World War II.”

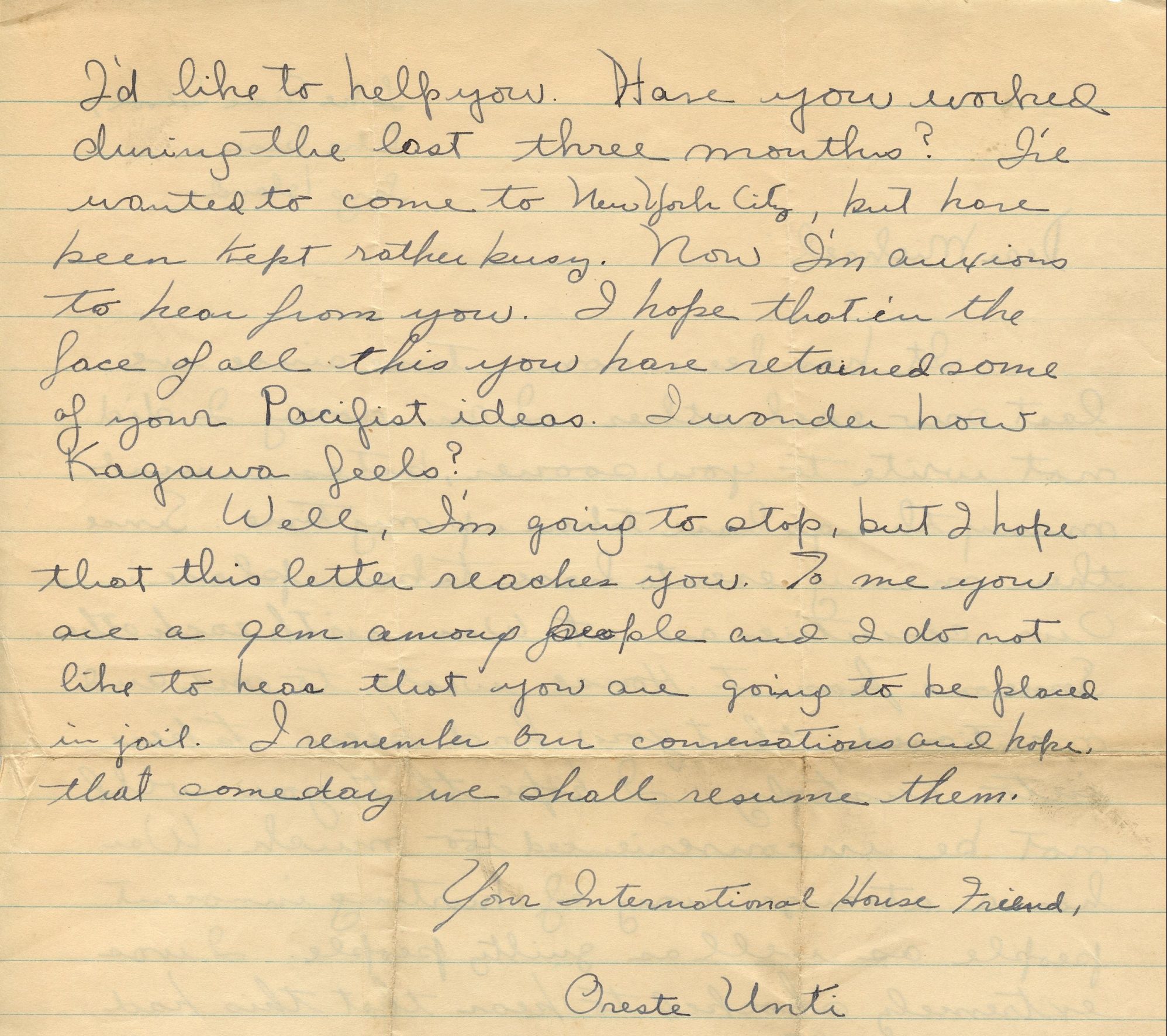

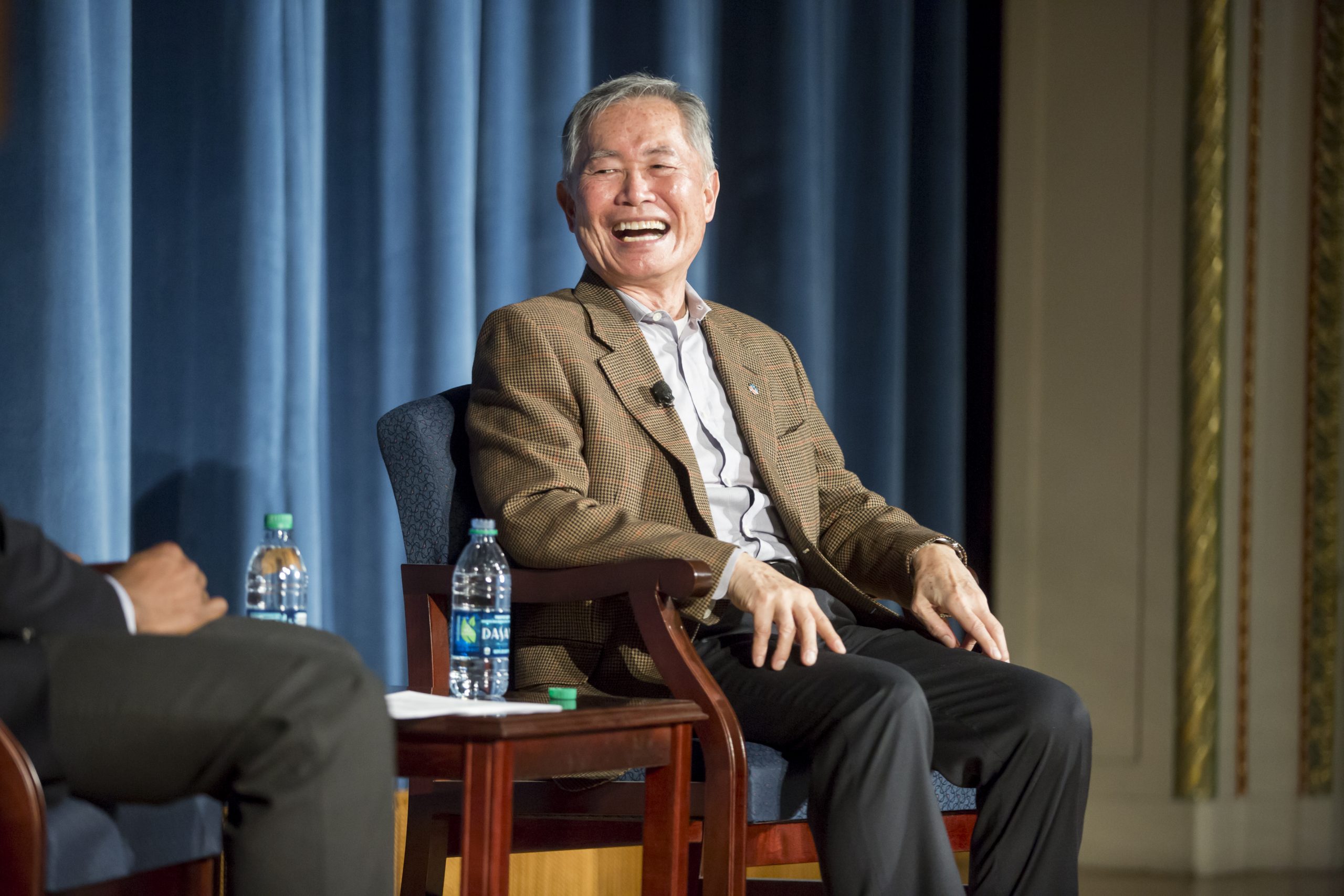

George Takei speaking in Davis Hall, 2016 / I-House Archives

The actor and activist George Takei is also actively involved in combating racism and raising awareness around Japanese American internment camps. When he visited International House in 2016, he discussed his new graphic novel, They Called Us Enemy. Written about his childhood years, at five years old, Takei witnessed two soldiers with bayonets approach their house in California. The army gave the family a mandatory “loyalty questionnaire,” resulting in their relocation to the maximum-security internment camp. After the war ended, the Takei family was released from the segregation center and left to fend for themselves on Skid Row in Los Angeles. Speaking at International House of his experience, Takei said, “people are fallible, but in a democracy, you don’t give up.” Unfortunately, activism and action are still necessary. America continues to contend with violence against AAPI and grapple with other issues like Islamophobia, hate crimes, and the deep-seated institutional racism that criminalizes Black and brown communities across our country. By looking back on this history and telling these stories, we have the power and responsibility to call out acts of hate and violence when others unfairly target people because of their race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, or other identities. Remembering Japanese internment reminds us how easily our civil liberties can be sacrificed in times of conflict and war.Clem Albers, Arcadia, California, April 6, 1942 / Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

*Additional research outside of the Archives could not find any further information regarding Saito’s fate. Further Reading- Frail, T.A., and Paul Kitagaki . “The Injustice of Japanese-American Internment Camps Resonates Strongly to This Day.” Smithsonian Magazine, Smithsonian Institution, 1 Jan. 2017.

- Goodman, James. “UR Exhibit Shows Lessons of Japanese-American Internment Camps.” News, Democrat and Chronicle, 8 Dec. 2016.

- Guilford, Gwynn. “The Dangerous Economics of Racial Resentment during World War II.” History Lessons, Quartz, 2 Feb. 2018,

Want to support the Archives? Click below! Have a question? Please email me at Archives@ihouse-nyc.org. Support the Archives